I think it’s safe to assume that everyone hates to be woken up at the middle of the night due to some crazy production bug. The most commonly adopted strategy to prevent those accidents from happening is to battle test your code. Test your code so hard and maybe you won’t be woken up at 3AM.

Automated tests are unquestionably perceived as fundamental for a sane and low-bug codebase nowadays. You create a set of tests (called a test suite), and you ensure the behaviour is the expected on every change (or at least before each deploy) by running the test suite over and over again. As a consequence, it’s normal that a team wants to know how good their tests are: do they need to add more tests, or is the test suite good enough already?

To help answering that question, code coverage (usually abbreviated to coverage) has been seen as the de facto metric for a long time when trying to assess the quality of the tests. But is it a good metric?

What’s coverage

I’ve always been a big advocate of having codebases with a strong test suite, which would give us a big degree of confidence that our logic is correct before making the code go into production. And, as almost everyone else, I used coverage as a metric to understand if the code was needing for more tests or not.

Code Coverage is a measurement of the percentage of code lines executed during the test suite.

But it wouldn’t take me long to understand that coverage was not a reliable metric. I remember the day I found a bug on a legacy component despite having the project reporting around 90% code coverage! Just by reading the tests it was obvious it were almost useless.

This was the day I stopped trusting coverage and started to question the utility of this metric (disclaimer: code coverage is not 100% useless, you just can’t trust it blindly).

There are also some subtle variations of the coverage definition which look at the percentage of executed functions, blocks, paths, etc. But let’s keep the definition under the number of lines for simplicity.

Why coverage sucks

Maybe you have already detected what’s wrong with coverage. If not, let’s look at the following snippet of code:

public boolean biggerThanTen(int x) {

if(x >= 10) {

return true;

} else {

return false;

}

}

and the corresponding unit test:

@Test

public boolean myTest() {

assertTrue(biggerThanTen(11));

assertFalse(biggerThanTen(9));

}

Can you guess what’s the value for code coverage? That’s right, 100%! But you can easily see that we are not checking the boundary value: what will happen if we pass 10 as the argument? It seems clear that despite the 100% coverage, our test suite has a major flaw!

But do you want to see an even more frustrating example? :)

@Test

public boolean myTestV2() {

biggerThanTen(11);

biggerThanTen(10);

biggerThanTen(9);

}

This test covers all the cases and reports 100% coverage, but… have you noticed we totally forgot to assert the function return value? And believe me, it wouldn’t be the first this would happen in real life!

Mutation Testing

By now you should be convinced that code coverage contains some real problems. We saw just 2 cases, but I’m pretty sure we could find a few more.

So what alternatives do we have?

Well, sometime ago I saw a talk around Mutation Testing (MT). Mutation Testing can be seen as the idea of introducing small changes (mutations) on the code and run the test suite against the mutated code. If your test suite is strong, then it should catch the mutation, by having at least one test failing.

The idea of introducing bugs/problems into our systems is not new: just remember of the famous Netflix Chaos Monkey, which introduces a failure in the system to check that the healing mechanisms are working as intended.

MT is based on two hypothesis:

-

The competent programmer hypothesis states that most software faults introduced by experienced programmers are due to small syntactic errors.

-

The coupling effect asserts that simple faults can cascade or couple to form other emergent faults. The coupling effect suggests that tests capable of catching first order mutations (single mutation) will also detect higher order mutations (multiple mutations) that contain these first order mutations.

Basic concepts

Before heading into some practical examples, let’s just go through some basic concepts of mutation testing:

-

Mutation Operators/mutators: A mutator is the operation applied to the original code. Basic examples include changing a

'>'operator by an'<', replacing'and'by'or'operators, and substituting other mathematical operators for instance. -

Mutants: A mutant is the result of applying the mutator to an entity (in Java this is typically a class). A mutant is thus the modified version of the class, that will be used during the execution of the test suite.

-

Mutations killed/survived: When executing the test suite against mutated code, there are 2 possible outcomes for each mutant: the mutant is either killed, or it has survived. A killed mutant means that there was at least 1 test that failed as the result of the mutation. A survived mutant means that our test suite didn’t catch the mutation and should thus be improved.

-

Equivalent Mutations: Things are not always white or black. Zebras do exist! On the mutation testing subject, not all mutations are interesting, because some will result in the exact same behaviour. Those are called equivalent mutations. Equivalent mutations often reveals redundant code that may be deleted/simplified. Just look at the following example:

// original version

int i = 2;

if (i >= 1) {

return "foo";

}

// mutant version

int i = 2;

if (i > 1) { // i is always 2, so changing the >= operator to > will be exactly the same

return "foo";

}

There are a few common types of equivalent mutations:

- Mutations in dead/useless code

- Mutations that affect only performance

- Mutations that can’t be triggered due to logic elsewhere in the program

- Mutations that alter only internal state

Mutation Testing in practice

Let’s get down to business! What kind of mutations can one expect? Let’s go through a few basic examples:

public boolean example1(int x) {

return x > 10; // MT can replace > operator for any other comparison operator

}

public int example2(int x) {

return x + 1; // MT can replace + operator for - operator

}

public Object example3(int x) {

return new Object(); // MT can replace return value by null

}

public int example4(String x) {

if(x.equals("random")) { // if condition can be replaced by true/false

return 0;

} else {

return 1;

}

}

Mutation Testing for Java

For the Java language, there’s an awesome MT framework called PIT. I’ve been experimenting it over the past few months on a small project, and it has caught a few interesting cases.

Why is PIT great? First of all it has a maven plugin (I know, this sounds like the basic, but most MT tools are more in research style yet, and are hard to use). Secondly, it is extremely efficient. PIT has been focusing on making MT usable, and it has been doing quite a good job IMHO.

To get started with PIT on a maven project you just need to add the maven plugin:

<plugin>

<groupId>org.pitest</groupId>

<artifactId>pitest-maven</artifactId>

<version>LATEST</version> <!-- 1.4.5 at the time of writing -->

</plugin>

And then you have MT available on your project by running:

mvn org.pitest:pitest-maven:mutationCoverage

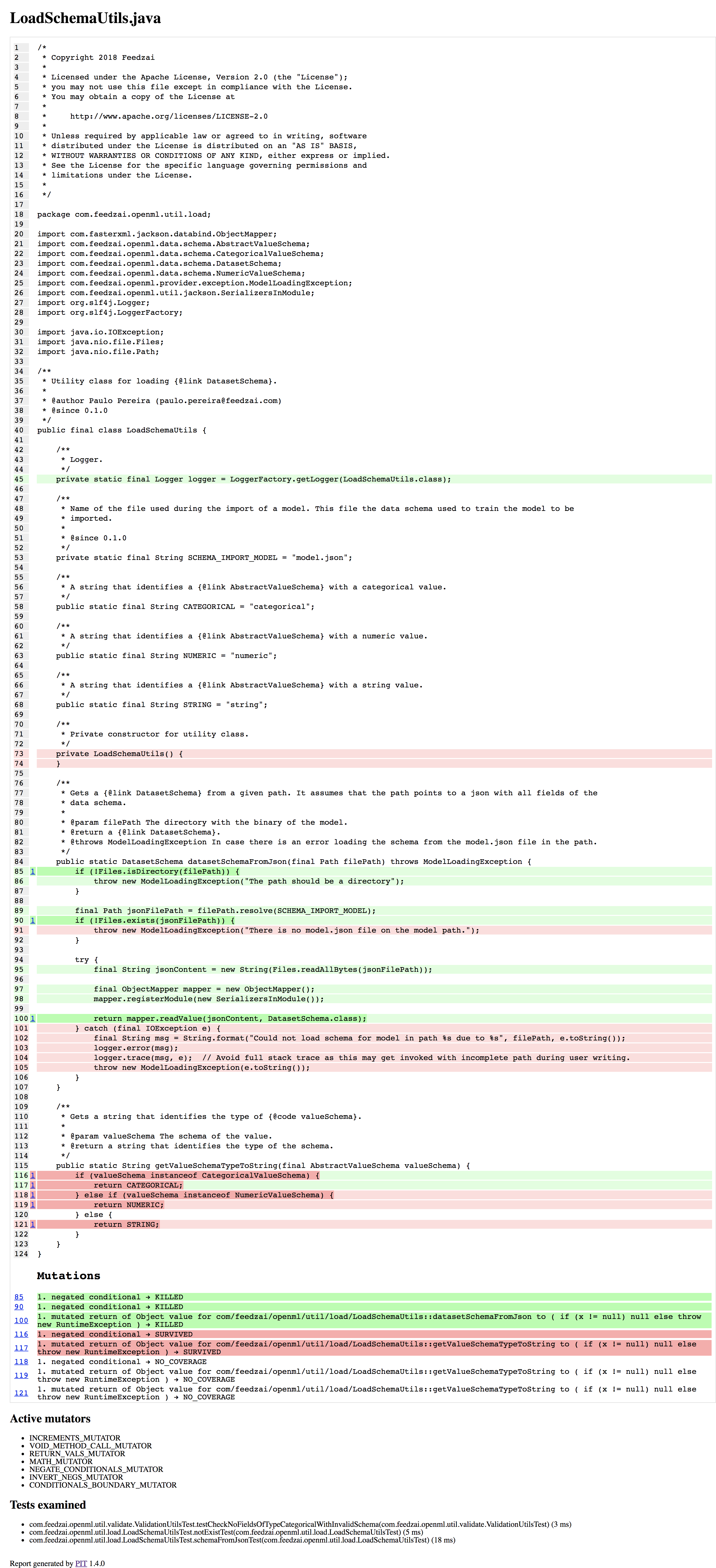

Check the HTML report generated at <base_dir>/target/pit-reports/<date>. Look at the following example to get an idea of what to expect:

For a given class, you’ll see green lines indicating that mutants were killed, or red lines, indicating that there’s no test covering that line or that a mutant survived. At the left side and at the bottom you can see the description of the MT outcome, that it’s usual self explanatory.

Tuning PIT

If you have a non-minimal project, you’ll probably need to tune your PIT configurations a bit.

The first configuration you may need, is to specify which classes should be mutated (maybe you don’t want to mutate DAOs), and which tests should be run (limit to your unit tests, and ignore integration tests). This can be achieved through the 'targetClasses' and 'targetTests' options:

<plugin>

<groupId>org.pitest</groupId>

<artifactId>pitest-maven</artifactId>

<version>LATEST</version>

<configuration>

<targetClasses>

<param>com.your.package.root.want.to.mutate*</param>

</targetClasses>

<targetTests>

<param>com.your.package.root*</param>

</targetTests>

</configuration>

</plugin>

If you want a more fine grained control, there are a few options: 'excludedMethods', 'excludedClasses', 'excludedTestClasses', and 'avoidCallsTo'. All of them are self explanatory, but if you want more details, look at the documentation.

Afterwards, depending on your coding style, you may feel the need to add or remove some mutators:

<configuration>

<mutators>

<mutator>CONSTRUCTOR_CALLS</mutator>

<mutator>NON_VOID_METHOD_CALLS</mutator>

<!-- <mutator>ALL</mutator> if you want to enable all mutators -->

<!-- see full list at http://pitest.org/quickstart/mutators/ -->

</mutators>

</configuration>

On smaller projects the 'ALL' option has worked well for me until now, but it’s a bit risky, specially if you do bump the PIT version and new mutators are introduced. But it’s a matter of testing what fits best on your project.

Some worthy configurations to improve performance include 'maxMutationsPerClass', 'threads', and 'timeoutFactor' (used for infinite loops detection).

Finally you may want to fail builds with lower mutation score than a given threshold:

<configuration>

<mutationThreshold>75</mutationThreshold>

</configuration>

MT problems

Mutation Testing is obviously not perfect. One of the biggest reasons for not being widely used yet it’s the fact that requires heavy computational power on bigger code bases: many possible mutants, many tests, more code to compile, etc. All of this increases a lot the amount of time running the mutations. PIT fights this problem with several optimizations regarding:

- Mutant generation

- Mutant insertion

- Test selection

- Incremental analysis

These topics will be covered in greater detail in the next article.

Another problem is that MT can easily create mutants that would make your tests fail in uninteresting ways, specially if you are not doing unit tests by the book. For instance, if you using an H2 database, MT can change configuration values that would make the connection fail. Mocks can also be problematic.

Fortunately, PIT allows you to specify which classes and methods should not be mutated, and it supports all the major java mocking frameworks. But other MT tools may not be as robust as PIT.

Extreme mutation

Extreme mutation is a another mutation testing strategy to simplify and to increase MT speed. It characterizes itself by replacing the whole method logic by an nullable block: in java we would have no code on void methods, a simple return null; statement on methods returning objects, or returning some constants.

The bases for extreme mutation are the following:

- a method is a good level of abstraction to reason about the code and the test suite;

- extreme mutation generates much less mutants than the default/classic strategy;

- extreme mutation is a good preliminary analysis to strengthen the test suite before running the fine-grained mutation operators.

The following snippet shows the original method before being mutated:

public Optional<String> getSomething(String baseStr) {

if(baseStr.length() > 10) {

baseStr += " -> this had more than 10 chars";

}

if(baseStr.startsWith("Why")) {

baseStr += ", and it was probably a question";

}

if (baseStr.contains("<secret code>")) {

return Optional.empty();

} else {

return Optional.of(baseStr);

}

}

and extreme mutation would transform it into:

public Optional<String> getSomething(String baseStr) {

return Optional.empty();

}

For PIT, there’s an engine that implements extreme mutation: descartes. You should totally try it in your project as a much faster alternative.

Conclusion

Code coverage has some flaws that don’t allow it to be a source of truth regarding the effectiveness of a test suite. Nevertheless, it acts as red flag: if you have 10% coverage, you are clearly not testing your code enough (unless you have a ton of boilerplate code - which is also a red flag).

Mutation testing has been evolving into a real candidate to become the de facto metric for assessing the quality of a test suite, defying the throne that has been occupied by code coverage until now.

Despite the problems associated with this concept, tools like PIT have been creating solutions and making MT a reliable solution to assess test suite strongness.

On the next article we will dig into the implementation details that make mutation testing performant and usable.

If you are interested in testing MT on other programming languages, have a look at:

- mutant for Ruby

- stryker-mutator, for Javascript, Scala, and C#

- scalamu, for Scala

List of other useful resources:

- A presentation on PIT, by it’s creator Henry Coles

- PIT resources section

- Maven plugin to support PIT on multi module projects

- PIT descartes engine

- A blog post on MT and PIT by Anthony Troy

And a presentation I gave at Pixels Camp 2019: