If you have built a minimal complex application, you very likely have more than one component (or service, or micro-service) on your architecture.

And depending on how you’ve built your application, you may have felt the need to communicate between those multiple components. Maybe to propagate a change, maybe to inform the state of the pipeline, or maybe to keep each component database synchronized. And how can you do that?

Perhaps you have decided to create a direct communication between them using java rmi, or a modern REST API between them. But what happens when the server you are contacting is down? Do you quit? Do you retry? And how do you know the server finished processing your request without blocking? What if you need to send the message to multiple servers?

If you implemented a very smart solution for all of these problems, then you probably should have looked at RabbitMQ or any other message broker instead. Message brokers allow you to create communication between multiple components, while maintaining them decoupled.

In this tutorial I want to go through the basics of RabbitMQ using some Scala snippets. While each message broker is somehow different, RabbitMQ is widely used, and most of them use the same base protocol: AMQP.

RabbitMQ

RabbitMQ implements the AMQP protocol, and it can be a good solution in several use cases. Besides the most basic use cases which we are going to have a look, there are also tons of plugins to extend its capabilities that may be useful: https://www.rabbitmq.com/plugins.html.

Starting a RabbitMQ instance

We will start by spinning up a RabbitMQ server instance. For that we are going to use docker because it makes everything easier. There are a few different docker images available, but we are going to use one that offers the management plugin already installed, which will help us understand what’s happening through our examples:

docker run \

-p 15672:15672 -p 5672:5672 \

--hostname my-rabbit --name rabbitmq \

rabbitmq:3-management

Now that we have a running RabbitMQ instance, we can access it’s manager UI through http://localhost:15672/. There we can see the overall state and statistics of our RabbitMQ instance.

Basic concepts

Before going into the examples, we need to go to the basics. When using RabbitMQ these are the main entities you should know about:

- One (or more) producer: an entity that sends messages to RabbitMQ

- One (or more) consumer: an entity that receives messages from RabbitMQ

- Queues: where messages live. When you send a message, the message will be kept in some queue. Messages are stored in queues, where consumers can process them.

- Exchanges: a indirection level between a producer and the queues. When you send messages, you send them to an

exchange. The exchange is then responsible for forwarding the message to the correct queues (0 or more queues).

My first RabbitMQ Producer

We are going to use the Java official client through this article despite the examples being in Scala, just because there are no official Scala clients.

We start by creating a connection to our RabbitMQ instance:

val factory = new ConnectionFactory()

factory.setHost("localhost")

val connection = factory.newConnection()

val channel = connection.createChannel()

Now we need to create a queue:

val queueName = "hello"

// if the queue survives a server restart

val durable = false

// if the queue can only be used from the original connection

val exclusive = false

// if the queue should be deleted by the server when no longer needed

val autoDelete = false

// other arguments - not needed for now

val arguments = null

channel.queueDeclare(queueName, durable, exclusive, autoDelete, arguments)

Finally we can go to the juicy part: sending messages!

val message = "Hello world! " + Random.nextInt(100)

val exchange = "" // It will use the default exchange

channel.basicPublish(exchange, queueName, null, message.getBytes)

And there you have it, you are now able to send messages to a RabbitMQ instance!

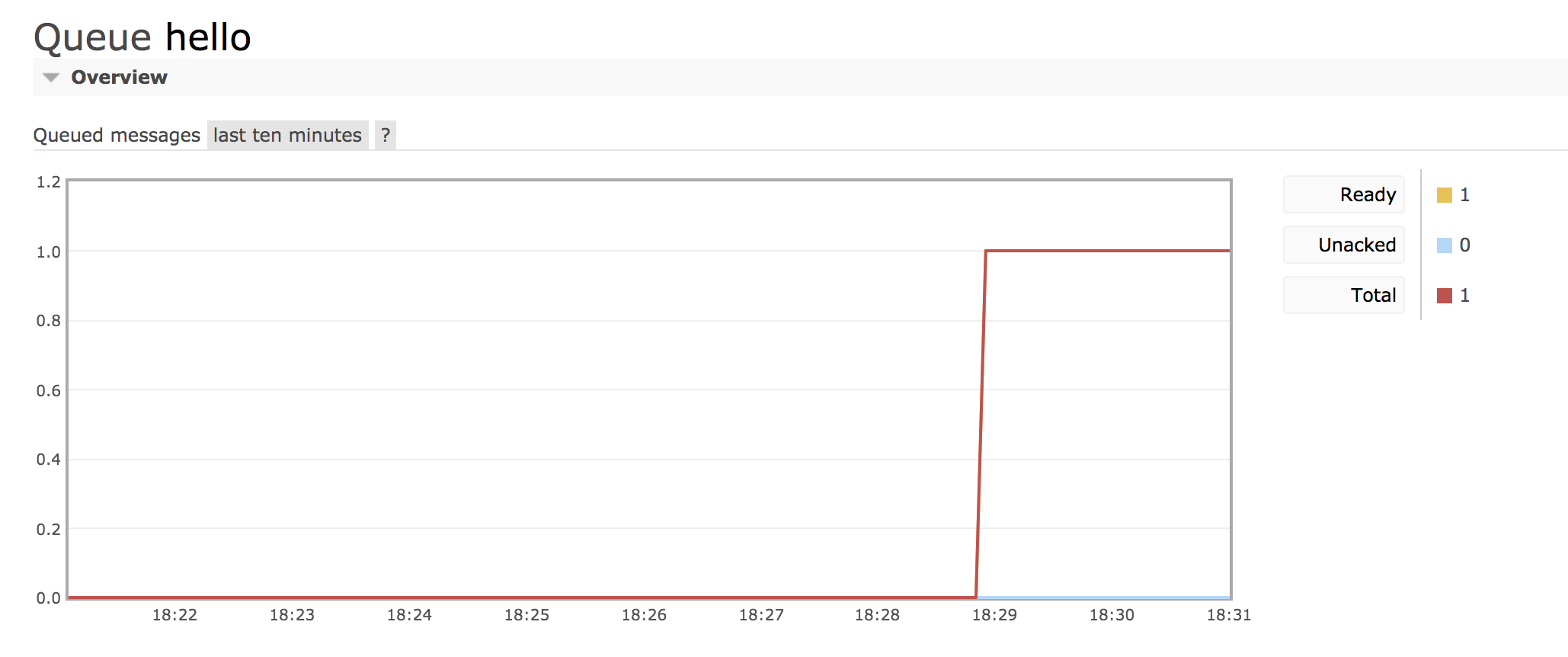

You can see it by yourself on the management UI, by going to http://localhost:15672/#/queues. Here we can see the queue we just created, and the queued messages, among many other metrics.

And if you go down the page, you will see a ‘Get Message(s)’ button, which allow you to consume the messages manually.

My first RabbitMQ Consumer

Now that we have messages in the queue, we want to receive and do something with those messages right?

We’ll start by connecting to the RabbitMQ instance just like we did on the producer:

val factory = new ConnectionFactory()

factory.setHost("localhost")

val connection = factory.newConnection()

val channel = connection.createChannel()

and we declare the queue as well. Since it’s an idempotent operation, you can repeat it in both producer and consumer, without any problem. It’s actually encouraged to do it so (it’s better to try to do duplicated work than to assume the queue is already created).

val queueName = "hello"

val durable = false

val exclusive = false

val autoDelete = false

val arguments = null

channel.queueDeclare(queueName, durable, exclusive, autoDelete, arguments)

To receive messages we must first remember that all of this is done asynchronously, so we work with callbacks (or handlers) here.

val callback: DeliverCallback = (consumerTag, delivery) => {

// we get the message body as a String

val message = new String(delivery.getBody, "UTF-8")

println(s"Received $message with tag $consumerTag")

}

// this is called when the consumption is canceled in

// an abnormal way (i.e., the queue is deleted)

val cancel: CancelCallback = consumerTag => {}

// autoAck specifies that as soon as the consumer gets the message,

// it will ack, even if it dies mid-way through the callback

val autoAck = true

channel.basicConsume(queueName, autoAck, callback, cancel)

These are the complete implementations for both the producer and the consumer:

import com.rabbitmq.client.AMQP.BasicProperties

import com.rabbitmq.client.ConnectionFactory

import scala.util.Random

object RabbitMqProducer extends App {

override def main(args: Array[String]) = {

val factory = new ConnectionFactory()

factory.setHost("localhost")

val connection = factory.newConnection()

val channel = connection.createChannel()

val queueName = "hello"

val durable = false

val exclusive = false

val autoDelete = false

val arguments = null

channel.queueDeclare(queueName, durable, exclusive, autoDelete, arguments)

val message = "Hello world! " + Random.nextInt(100)

val exchange = ""

channel.basicPublish(exchange, queueName, null, message.getBytes)

println(s"sent message $message")

channel.close()

connection.close()

}

}

import com.rabbitmq.client.{CancelCallback, ConnectionFactory, DeliverCallback}

object RabbitMqConsumer extends App {

override def main(args: Array[String]) = {

val QUEUE_NAME = "hello"

val factory = new ConnectionFactory()

factory.setHost("localhost")

val connection = factory.newConnection()

val channel = connection.createChannel()

channel.queueDeclare(QUEUE_NAME, false, false, false, null)

println(s"waiting for messages on $QUEUE_NAME")

val callback: DeliverCallback = (consumerTag, delivery) => {

val message = new String(delivery.getBody, "UTF-8")

println(s"Received $message with tag $consumerTag")

}

val cancel: CancelCallback = consumerTag => {}

val autoAck = true

channel.basicConsume(QUEUE_NAME, autoAck, callback, cancel)

while(true) {

// we don't want to kill the receiver,

// so we keep him alive waiting for more messages

Thread.sleep(1000)

}

channel.close()

connection.close()

}

}

At this moment you already have a decoupled pair of services that can exchange messages asynchronously. Give it a try and play at your own rhythm now!

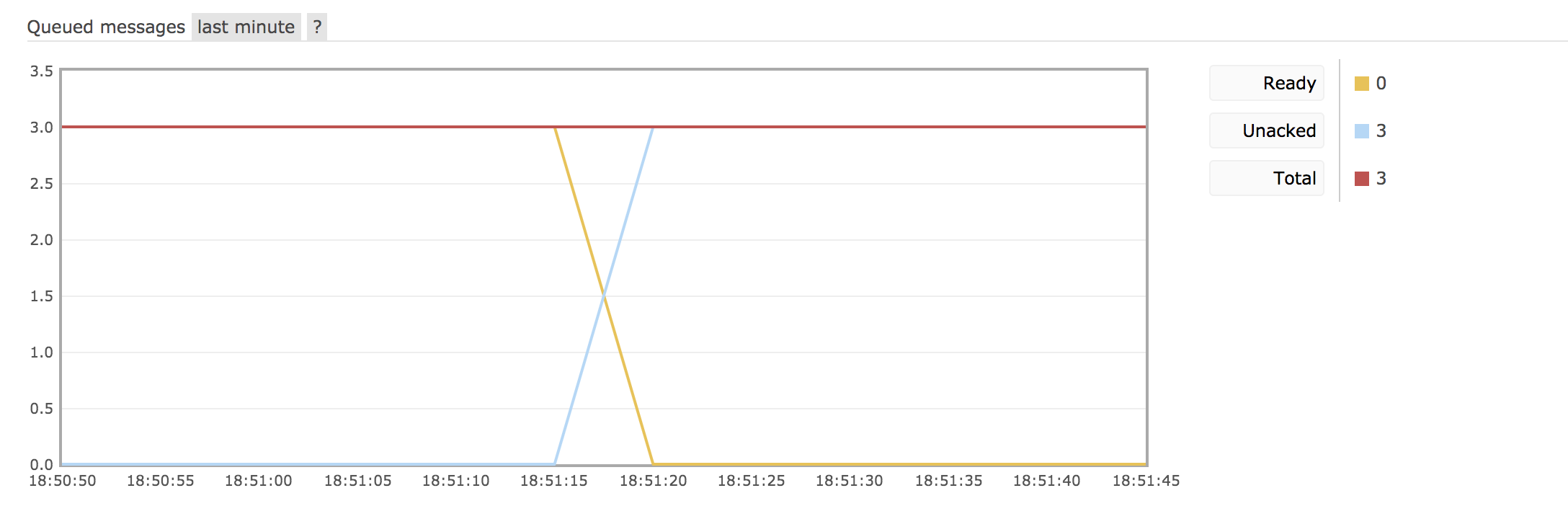

Manual Ack

As we saw, we have set autoAck as true. This means that whenever a message is received (consumed), an automatic ack will be sent, and the message will be deleted from the queue. But often the receiver will do a complicated processing of the message, and can fail mid-through. In such cases, the message will be lost forever. Unless you disable autoAck and do it manually:

val callback: DeliverCallback = (consumerTag, delivery) => {

val message = new String(delivery.getBody, "UTF-8")

println(s"Received $message with tag $consumerTag")

// manual ack

channel.basicAck(delivery.getEnvelope.getDeliveryTag, false)

}

val cancel: CancelCallback = consumerTag => {}

val autoAck = false

channel.basicConsume(queueName, autoAck, callback, cancel)

If you forget to do the manual ack, the message will stay in an ‘Unacked’ state until the connection is closed. If the connection is closed, and you start the receiver again, and you’ll that the message will be received again.

Fair dispatch

What we have seen so far allow us to use RabbitMQ to create a Work Queue system (producers submit tasks to be processed by many receivers/workers). If you use RabbitMQ as a Work Queue, you may find a problem on our simple setup until now.

RabbitMQ by default dispatches messages in a round-robin strategy. This means that if you have 2 consumers, all odd tasks will go to one of them, and all even tasks will go to the other. With a bit of unlucky, all the heavy tasks may end in one or in a small group of workers, while others are doing nothing. This is obviously a waste of resources and will impact your system performance.

Luckily RabbitMQ has a simple tuning knob to change the default behaviour. On the receiver you just need to add:

channel.basicQos(1)

val autoAck = true

channel.basicConsume(queueName, autoAck, callback, cancel)

This setting imposes a limit on the amount of data the server will deliver to consumers before requiring acknowledgements. In the example above, the server will only deliver 1 message and wait for the ack before delivering the next one. Thus, the server will always prefer to send messages to free receivers, making the workload better distributed.

Publish-Subscribe

Until now we have been using RabbitMQ as a communication mechanism to deliver messages to a single consumer. Very often you want to deliver one message to multiple consumers. This is what we typically call a Publish-Subscribe architecture.

A real and very common scenario consists in an micro-services architecture, where each service has its own database, but that may contain duplicated information across those databases (for instance, users information).

In such cases, we need to keep the databases synchronized, so we want to send a message to all (or many) other services. RabbitMQ offers such possibility very easily by using exchanges.

We have been sending and receiving messages through queues, but that’s quite limiting. We can use exchanges to achieve our purpose. An exchange is the entity responsible for receiving messages from the producer and send them into the correct queues.

There are 4 different types of exchanges:

- direct - delivers messages to queues based on the message routing key;

- fanout - delivers messages to all queues bound to that exchange, ignoring the routing key.

- topic - delivers messages to queues based on the matching between a message routing key and the pattern that was used to bind a queue to an exchange;

- headers - ignores the message routing key, and delivers messages based on the message header attributes;

To enable the Pub-Sub pattern, we will to use the fanout exchange.

On the producer side, we stop sending messages directly to a queue, and send to an exchange instead:

val exchange = "my-exchange"

channel.exchangeDeclare(exchange, "fanout")

val message = "Hello world! " + Random.nextInt(100)

val routingKey = ""

channel.basicPublish(exchange, routingKey, null, message.getBytes)

And on the consumer side we create a queue and we bind it to the exchange:

// create non-durable queue with random name

val queueName = channel.queueDeclare().getQueue

val exchange = "my-exchange"

val routingKey = ""

channel.queueBind(queueName, exchange, routingKey)

Want to see it in action? Just spin up multiple consumers (two are enough) and one publisher using the snippets above. You will be able to see that a message is delivered to all the consumers.

Fine-tuning messages

In the previous example we made every message sent to an exchange being received by all queues bound to the exchange. While you can filter using custom logic on the service code, RabbitMQ offers a way to filter them in a easier way: using routing keys.

As we saw before, there are 4 different exchange types. If you use fanout, the routing keys will be ignored. If you use headers, the filtering is done on the headers attributes. So we are left with 2 exchange types to explore:

direct- in this exchange, we can use routing keys to filter which messages from an exchange will be sent to each bound queue.topic- this exchange is a little more complex as it decides which queues to send messages depending on the given pattern. Let’s go through it!

Topic exchanges: When using topic exchanges the routing key is seen as a pattern. This pattern must be a list of words delimited by dots. It works very similar to a direct exchange, because messages are delivered to queues that match the routing key, but it allows 2 special patterns:

- * (star) can substitute for exactly one word.

- # (hash) can substitute for zero or more words.

I totally recommend the example on the official documentation to better understand this. But let’s go through it step by step:

Considering our domain is about animal species, let’s assume we define the topic pattern as ‘<speed>.<colour>.<species>’. We now create 2 queues:

- Q1 is bound with ‘

*.orange.*’, which means it will receive all messages describing orange animals. - Q2 is bound with ‘

*.*.rabbit’ and ‘lazy.#’, which means it will receive messages describing all rabbits, and all lazy animals.

Custom class messages

For the final part we want to make our example somehow production-usable. One of the missing points on our previous examples was structured messages. Sending messages as String may sound cool, but as your app growths, you will want to have more complex messages. If you look carefully, you saw that we don’t send Strings directly into RabbitMQ. Instead we send the corresponding bytes. So if you want to send another POJO, you just need to convert it into bytes as well.

Here we are going to make use of Scala case classes. Case classes are perfect for this, because they are serializable. If you have a serializable class, you can easily convert it into bytes with the following code:

object SerializationUtils {

def toBytes(obj: AnyRef): Array[Byte] = {

val baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream()

val oos = new ObjectOutputStream(baos)

oos.writeObject(obj)

val bytes = baos.toByteArray

oos.close()

baos.close()

bytes

}

def fromBytes[T](bytes: Array[Byte]): T = {

val bis = new ByteArrayInputStream(bytes)

val ois = new ObjectInputStream(bis)

val obj = ois.readObject().asInstanceOf[T]

bis.close()

ois.close()

obj

}

}

Java serialization is highly controverse, but for our demonstration purposes works. If that’s a realistic concern for you, check out FST or kryo for instance.

Now that you know how to convert any serializable class into bytes, you can use more expressive messages very easily.

Final Remarks

This was a very introductory look into RabbitMQ, and into message brokers in general. Each implementation provides different capabilities, and some of them, like RabbitMQ, still offer a wide range of plugins. Nevertheless, message brokers allow you to decouple communication between components of your application, making it easier to scale when needed.

As such, you should take message brokers into account when designing your new architecture.