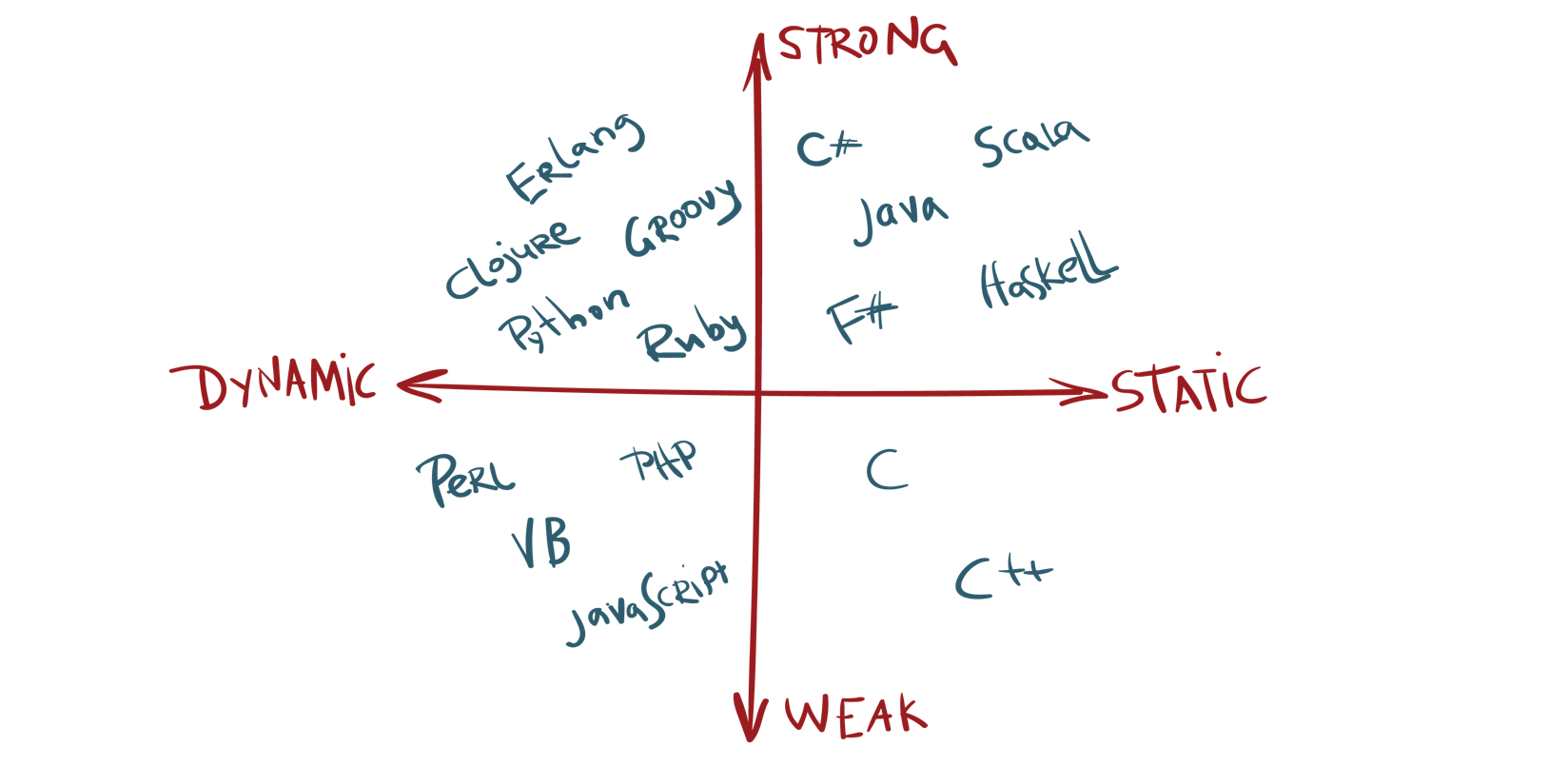

Statically vs dynamically typed languages is one of those eternal wars among developers.

One of the arguments that statically typed programming language developers (like Java, Scala, and Haskell) often use when arguing to defend their choice, is that the type system helps catching many bugs before the code goes into production.

I don’t want to discuss if you should use statically or dynamically typed languages, but I would like to show that we don’t always leverage the type system as much as we could on statically typed languages. The common pitfall happens by using the type java.lang.String to encode many different concepts, allowing some easy-to-prevent bugs.

Statically typed languages overview

Statically typed programming languages characterize themselves by having a compilation process that includes a type checking phase, which ensures the variables and functions are the type they are declared (this happens even with type inference, where there’s a type, but it’s not explicitly specified by the user - let’s ignore type inference for simplicity).

A basic code example in C, which is statically typed:

int x = 5;

char y[] = "37";

char* z = x + y;

And an example in Ruby, which is dynamically typed:

x = 5

y = "37"

As you can see, in C you have to specify the type of the variables, and in ruby you don’t.

What’s the advantage of types?

You are probably thinking the Ruby example is way more clean and less cumbersome. I mean, it’s obvious: in C you have to write the type information every time, and in Ruby you just create a variable. Typing 3 more letters for each variable declaration is a lot, I have to agree with that. That’s why both Scala and Kotlin, and now Java 10 brought type inference into the game.

But having the compiler checking the code with a type checker brings an huge advantage as it finds potential bugs really early in the development process. This becomes more clear as the codebase grows.

While in dynamic languages (as Javascript) you may need to defend your code against receiving the wrong type, or some typos that break your code (yes, I know, a good test suite would also catch these bugs) in Java you know the variable has the expected type:

// javascript example

> function stringSize(str) {

return str.length;

}

> stringSize("str")

3

> stringSize(42)

undefined

// java example

> public static int stringSize(String str) {

return str.length();

}

> stringSize("str")

3

> stringSize(42)

compilation error: incompatible types: int cannot be converted to String

Using String as types

In Java (and other Java interoperable languages) there’s a java.lang.String class, intended to represent text variables.

Developers typically use Strings to represent names (for instance Person.name). Ids are also commonly (and wrongly) represented as Strings.

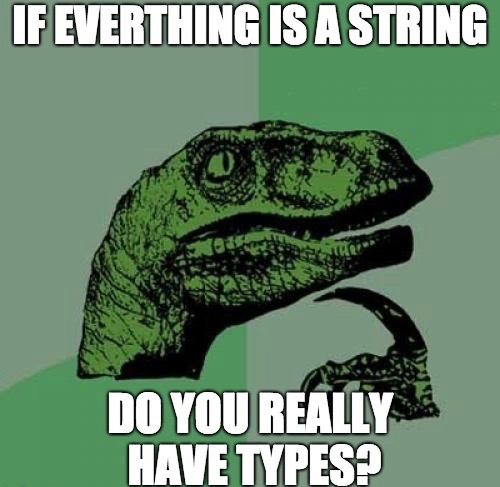

But what’s the problem with encoding a person’s name as a String? At first sight it makes sense, and it’s not an awful idea. But soon we are going to start encoding Id’s as Strings. And descriptions as Strings. And now everything is a String in your codebase.

And this is why you should be really careful when defining your domain as a String. The type should have a semantic meaning associated: is a book ISBN and a book description the same? No. So why would you encode both with the same type?

I’ve seen my share of bugs due to using the wrong semantic type: calling a function with a movie ID when it should have been an actor ID for instance, or passing a person’s name where it should have been the person database ID.

All because both types were Strings. And I guarantee it will happen to you too, sooner or later.

Avoiding Strings

When coding in Java, I always try to create appropriated POJOs to represent each type, but unfortunately the amount of required boilerplate makes me not using the most appropriated type (yes, there are tools to help with this, each with some drawbacks). But in Scala (and Kotlin) we have easy and native ways to avoid using Strings with case classes (or data classes in Kotlin):

// note that the 'Person.' prefix can be omitted

case class Person(name: Person.Name, age: Person.Age, id: Person.Id)

object Person {

case class Name(value: String) extends AnyVal {

override def toString = value.toString

}

case class Age(value: Int) extends AnyVal {

override def toString = value.toString

}

case class Id(value: String) extends AnyVal {

override def toString = value.toString

}

}

As you can see, the amount of code required to create appropriated types is really small. Take into account that I decided to declare the Person related types as inner classes in the companion object just to avoid class name clashing. It’s perfectly acceptable to declare those helper types as top classes (but not as readable IMHO).

Performance considerations

It’s perfectly reasonable if you have performance concerns on this approach. We are boxing every String and primitive type. That’s where Scala Value classes can help you out. In summary, Value classes are a mechanism in Scala to avoid allocating runtime objects.

Java has also been conducting research on that through Project Valhalla.

Nevertheless you should always take into account that high performant code may require us to drop some good coding practices. My recommendation is to create a clear separation on high performant code and “regular” code. And use comments to make explicit everything that’s happening on (sometimes obscure) high performant code.

Conclusion

If you are in favour of using statically typed programming languages, then leverage all the power of the type system!

Encoding a gazillion of different types into Strings won’t help you a lot, and sooner or later it will bite you. If you have the advantage of using languages which provide easy constructs for new types, you have no excuse to shoot yourself in the foot.