This post was originally published on Codacy blog by me:

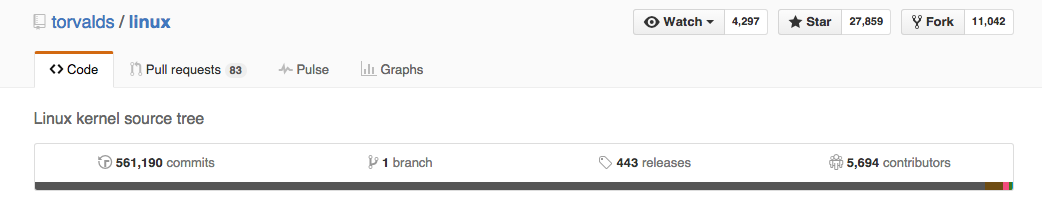

I believe the Open Source movement is the biggest breakthrough in software development. Open Source has allowed many projects to increase the number of contributors (and contributions) to unreachable standards for any enterprise. Just take a look at the Linux kernel, which counts with 500,000+ commits and 5,600+ contributors.

In this evolution, platforms such as SourceForge, Google Code, Bitbucket, and especially GitHub played a fundamental role connecting developers all around the world and wide-spreading remote contributions.

Personally, I had the opportunity of working on Open Source projects while working at FenixEdu. At Codacy, we also have several open source projects. We have some docker engines to support our code analysis, we have some code coverage tools that help users to import coverage reports to Codacy, and we also have projects like our Scala clients for Bitbucket API and Stash API. While the last two should be far more interesting to the general community, having all of them open source allows users to report problems and get fixes way faster. It’s not uncommon to have users contributing to improve our tools. A good example is our python-codacy-coverage project which has received valuable help from the community.

Lately we have also been devoting more time to our open source projects. We have been busy on providing proper documentation and taking a careful look for created issues and pending pull requests.

In this process we realized that it is very common to have users who want to contribute to the Open Source movement but don’t really know how to start, so we decided to collect some good practices for all of those who want to contribute to the Open Source movement and simply don’t know how to.

If you are an open source project owner:

- Create a README file, providing an overview about the project as well as some usage instructions. This may include some project badges (look at our node-codacy-coverage project as an example) that visually indicate several stats. I usually include the build status, current release version, coverage, and Codacy project grade. It is also a common practice to include a Troubleshooting section, for common errors and how to solve them.

- Create a CONTRIBUTING file, providing instructions on how to contribute to the project. Take a look at this Codacy project, for instance.

- Automate tasks. A new contributor may not be fully into the project. By providing a simple mechanism to compile, run, and test, he will be much more efficient. An easy way to quickly provide a fully configured environment may be to use dockers.

- Integrate with a Continuous Integration (CI) platform. The CI helps you by assuring the contributions don’t break your project. CI should be built upon tests - a piece of code all managers like to postpone when the sprint gets short - that can be run to ensure no previous code has been broken by recent changes. There are plenty of CI platforms available. Among the most used ones we have CircleCI, Travis, Bamboo, CodeShip, and Jenkins.

- Define coding standards, usually followed by format settings for the most common IDE(s). At Codacy we have our own IntelliJ settings so we can reduce visual pollution on commits diffs. Codacy can be used to automatically review code, and integrated in development workflows, so you don’t waste time enforcing coding standards.

- Create issues for known/reported problems. This allows contributors to be aware of contributing opportunities. Also, make an effort to keep issues updated, i.e., answer existing comments, close solved issues, correctly label them, and so on. Labels can help you say which problems won’t be solved, which you need some help with, which ones are bugs, performance, improvements, etc.

- Watch incoming pull requests. Contributions will appear in the form of pull requests. Don’t let a pull request remain ignored for weeks without a single word to the author.

- Tag your releases appropriately. This way users can inspect the code at the state of each release, allowing them to debug some eventual problem. GitHub provides documentation on tags which may be useful. Also, semantic versioning is the current standard to project versioning. Among other properties, users are immediately aware what kind of changes the new version introduces. There is also this great post on working with semantic versions, check it out to better understand the topic.

- Choose a license. It is very common not to have a license in your Open Source. Mostly because no one really understands licenses. Choose a license demystifies all these ghosts. If you don’t care about it, use the MIT License, which is one of the most permissive ones out there. If you really want to check the differences between existing license, check this list.

- Ask for help if you can’t manage all the work of maintaining the project. There are always users available to help maintaining a project. Discuss the idea/vision of your project so you both get aligned before starting to work together.

If you want to contribute to an open source project:

It should be pretty easy if the project owners have followed the previous guidelines.

- Read all the documentation they made an effort to create (README, and specially CONTRIBUTING, if present). The documentation should provide enough info for you to start.

- Fork the project

- Announce you are on a issue. If you are trying to solve a reported issue, comment that you intend to solve it, and possibly discuss with the project maintainers the best approach before starting to code

- Create a new branch on your fork and code your solution (it’s always good to add/fix tests)

- Open a pull request after having pushed your changes.

- Iterate your changes as the project maintainers comment your code

- Your pull request should be accepted as you converge to an accepted solution

If there is no documentation about how to contribute, try to make the most clean and understandable code so reviewers can have their work eased. Put yourself in a reviewer situation. Would you like to review your own code? Would you like to have that code in your project? If you can’t find a nice solution, remind that the community is always there to help.

There are also some discussions about what are the best practices to contribute through pull requests. While some may argue that a pull request should contain a single commit, gathering all changes and making sure that every commit is in a deployable state, others defend that a pull request may be logical split into several smaller chunks (commits) , making it easier to review the pull request. Check some discussions here, here, or even in reddit about pull requests best practices.

That is all you should need if you want to start contributing to Open Source projects.

First timers

Still on Open Source contributions, Kent C. Dodds (maintainer of angular-formly), wrote a very interesting article, where besides some good practices, Kent introduces a awesome new initiative: contributions to first timers only.

First timers are developers who never had the change to contribute to a Open Source project, developers who want to make their first ever contribution.

This initiative creates a soft entry to Open Source for those who have been looking for the opportunity but may have been frighten by the process. This also increases the number of open source contributors in the community, making every project to benefit from it in the long term. That is why more projects should think about creating opportunities to first timers.

If you are looking into your first Open Source contribution just search for it in GitHub.

And keep in mind, if you want to improve your code quality, Codacy is fully integrated with GitHub and Bitbucket, and it is free to Open Source