This is the third of a series of Git related posts. After covering the basic Git concepts, and starting with simple Git usages, it’s time to go one step further: use Git power to check your project history, managing several workflows through different branches (don’t be scared of merge conflicts), understand the difference between git checkout and git reset, and another couple of tricks.

This article should help you understand how to use several Git features. From it’s powerful branching mechanism, to the dreadful conflict resolution, not forgetting the misunderstood differences between checkout and reset, and the ability to see history through logs. All of this will reveal very easy.

The next post will cover collaborative environment workflows, as what can be seen in the open source movement. Forks, pull requests, remotes, rebases, and many other concepts will be approached.

The past is here

The first thing I want to approach is the git log command. Believe me, you will use it every single day. It can be useful to see where did you left your work in the previous day, to see who has been working on your repository, and so on. The git log command is your entry point to the past.

As every other git command, git log has tons of (useful) flags. Many of them I’ve never used nor seen. And you probably won’t see them too. Depending on your preferences, you will end up using 2 or 3 command variations regularly.

The simplest

Just go to any git repository (not really any, more like any repository that already has some commits), and try it by typing: git log. You should see something like:

$ git log

commit f5d170a54d051aa87516f1ea66e43f1c8eb40fa5

Author: pedrorijo91 <author@email.com>

Date: Tue Apr 11 20:00:12 2017 +0100

Fix scala interview post from comments

commit bbe9531c1f63968eecfb799b6be4657e3bdaf2f9

Author: pedrorijo91 <author@email.com>

Date: Tue Apr 11 19:59:34 2017 +0100

Fix copyright

commit fdb72a2076e7d62679051a700ae2fc06fbdd6993

Merge: aedeae4 5b3da5d

Author: pedrorijo91 <author@email.com>

Date: Fri Apr 7 20:39:53 2017 +0100

Merge pull request #46 from pedrorijo91/seo/htmlLang

Add html lang EN

This is the simplest log command. It shows the commit hash, the author, the date, and the commit message. Eventually, if it’s a merge commit, it can show more info, like the hash of its ‘parents’.

Advanced log usages

While it’s very useful, I rarely use the basic log command. I don’t like the fact it uses too much space. I prefer to see more commits, and only the relevant information. If you type git log --oneline you will get more succinct information about what has been happening in the repository:

$ git log --oneline

94c588c Merge pull request #49 from pedrorijo91/feature/version

44e392e Add version div to footer

12e13db Merge pull request #48 from pedrorijo91/fix/scalaInterview

c6c41eb Merge pull request #47 from pedrorijo91/fix/copyright

f5d170a Fix scala interview post from comments

bbe9531 Fix copyright

fdb72a2 Merge pull request #46 from pedrorijo91/seo/htmlLang

5b3da5d Add html lang EN

And now you can have a quick look and know what changes have been introduced. But maybe you want to know who are the commits authors? You can specify the information using git log –pretty=format:<string>. I have personally defined my own log format (with pretty colors!):

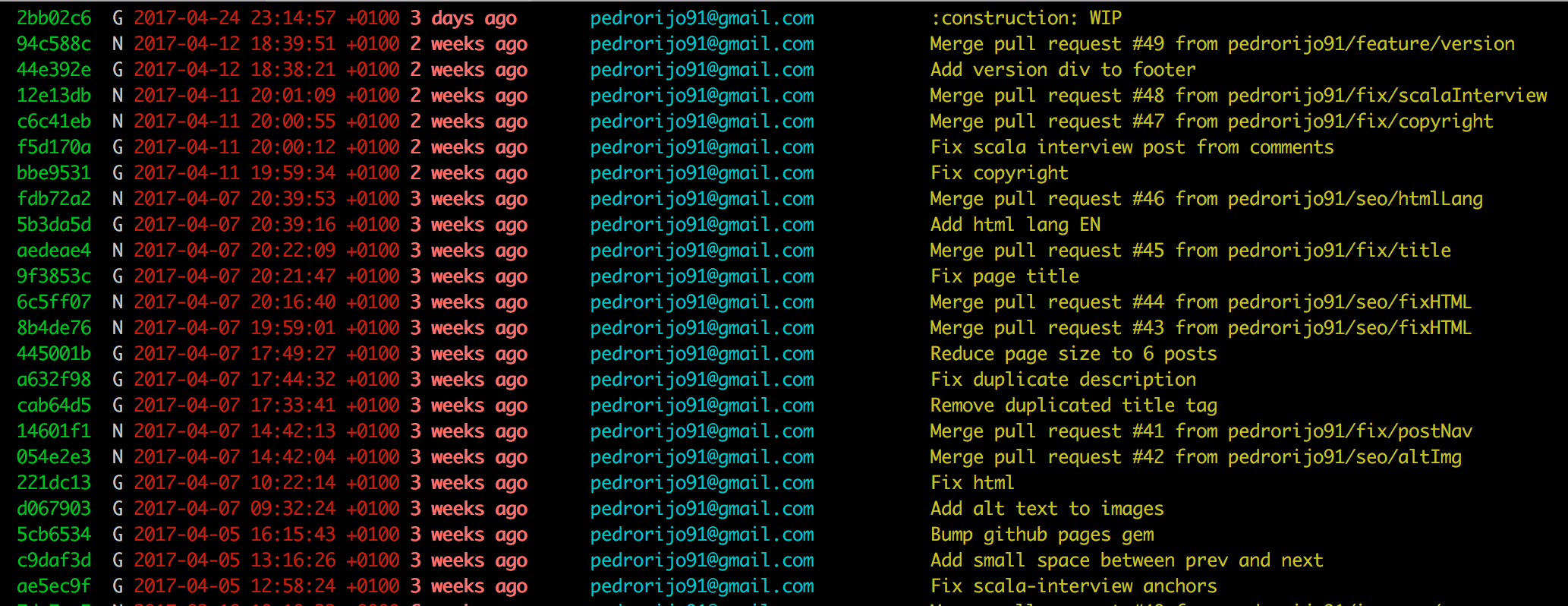

git log --format='%Cgreen %h %C(white) %G? %Cred%ai %C(bold)%<(15)%ar %Creset %C(cyan)%<(30)%ae %C(yellow) %s'

This will produce a line with several components for each commit:

- commit hash (

%h) - signed commit? (

%G?) - author date (

%ai) - author relative date (

%ar) - author email (

%ae) - commit title message (

%s)

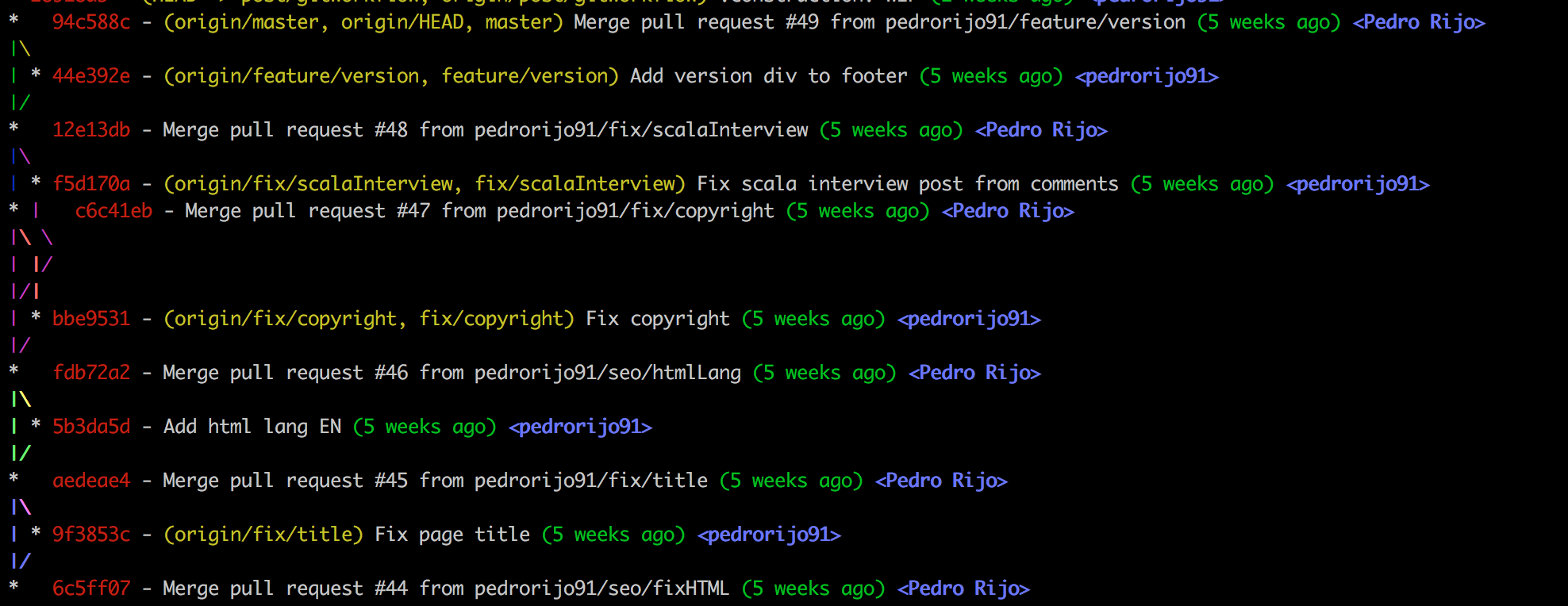

But most of us really like that graph that we can see on BitBucket for instance. Git is also able to output a similar graph to the terminal. Just type (I know, it’s really a big command…):

git log --graph --pretty=format:'%Cred%h%Creset -%C(yellow)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr) %C(bold blue)<%an>%Creset' --abbrev-commit --date=relative

So feel free to create your own. Just make it useful for yourself. And remember to have a look at the git log command documentation. You may find some useful flag.

Log filtering

I guess we all have been in situations where you’d like to be able to select just some commits from the history. The log command includes the possibility to filter the displayed commits. Basic filters include:

- limit number of commits:

git log -3(will limit to 3 most recent commits) - select by date:

git log --after="2014-7-1"(there’s also a --before flag) - filter by author:

git log --author="pedrorijo91" - find by commit message:

git log --grep="MESSAGE" - filter by commits that changed a specific file:

git log -- foo.scala bar.java(will show only commits that affected foo.scala or bar.java files) - filter by commit content:

git log -S"A random line of code"(will filter commits where this line was affected) - by range:

git log master..feature(shows all commits that are on the feature branch and not in the master branch). This is specially useful if you use a development and a master branch and you want to see what is not yet in production for instance.

This and other log filters are very well described on this Atlassian git log tutorial.

Branches

As I already said, branches are one of git core features, and the git branching mechanism is one of it’s strongest adoption points. With branches, you can be working on some feature, be alerted by an ultra urgent production bug, change branch, do a quick fix, and go back to your feature work. All of this without any complicated technique.

Creating new branches

In order to create a new branch you just need to type:

$ git branch <BRANCH_NAME>

Now go ahead and see your new branch by asking git to list all branches:

$ git branch

* master

<BRANCH_NAME>

As you can see, there’s a special symbol before the master branch. This is just a visual clue to know in which branch you are currently.

Changing branches

If you want to change to a specific branch it is also very easy:

$ git checkout <BRANCH_NAME>

Very frequently you will want to create a new branch, and at the same time, change to that branch. Git allows us to do that with a very small shortcut:

$ git checkout -b <NEW_BRANCH_NAME>

the -b flag will create the new branch before checking out to the branch you just passed as an argument.

Deleting old branches

From times to times you will notice your project is full of old branches. Deleting git branches is not as simple as the previous operations.

Keep in mind that a branch may exist in your local git repository, or/and in the remote repository (meaning the branch was already pushed by someone).

Deleting a local branch is very easy:

$ git branch -d <BRANCH_NAME>

Deleted branch <BRANCH_NAME> (was <COMMIT_UUID>).

The command returns as output a delete confirmation, with the information about the last branch commit.

This will remove your local branch, but if the branch to be deleted is on the server/remote then you should do:

$ git push origin --delete <BRANCH_NAME>

Merge

Now that you know how to work on independent branches you should be asking yourself ‘But how do I bring my changes from one branch into another?’.

The easiest solution is to use Pull Requests (if you are using GitHub or Bitbucket, or merge requests if you are using GitLab). Pull Requests are a concept introduced by GitHub, that basically tells other developers ‘Here are my changes. Can you have a look, and if they are ok integrate them into the main branch?’.

If/when someone accepts the pull request and chooses to click on the ‘Merge Pull Request’ button, they are merging your changes back into the main branch (actually you can do a Pull Request for any branch, but that’s a minor detail).

But you can make your changes into another branch using only git, without any Pull Request or any other GitHub features:

- using git rebase, which is a little more complicated, and that allows you to rewrite git history. I will approach rebase on a future post.

- using git merge, which brings the changes from one branch into another. This is the solution I would like to cover for now.

The merge command is quite simple:

$ git rev-parse --abbrev-ref HEAD # will output the current branch

master

$ git merge myHotFixBranch # will bring changes from myHotFixBranch into current branch (master)

Updating 86cba7a..29dc020

Fast-forward

<SOME_CHANGED_FILE> | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

As you may have already noticed, the merge command outputs some information. You can see the commit hash for the current commit (86cba7a), and the hotfix branch top commit hash (29dc020), as well as the files with their changes stats.

Besides all of those details, it is visible a line containing ‘Fast-forward’. What does it mean? It is just a special kind of merge, where the new commits from the other branch are just descendants of the current branch top commit, meaning you keep a linear history. Simplifying: since you created the new branch, no other commits have been done to the original (the first one).

It may happen that the current branch also got some commits, meaning the previous situation no longer happens. In such cases, a new commit will be created, called a ‘merge commit’. If both branches changes don’t intersect, git will perform the changes for you. If not, then git will warn you about some conflicts that you will need to tell git how to solve:

$ git merge otherBranch

Auto-merging <SOME_FILE_CHANGED_IN_BOTH_BRANCHES>

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in <SOME_FILE_CHANGED_IN_BOTH_BRANCHES>

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Merge conflicts

This is probably one of the most feared situations in git. So many developers hate to have conflicts when working on a git repository. It is important to understand merge conflicts so that you don’t get anxious at every merge command.

There are 2 ways to solve conflicts:

- manually, making changes on each conflicted file;

- automatically, by using some merge flags to tell git which strategy to choose when dealing with merge conflicts

Solving conflicts manually

Now that you got into a merge conflict, how can you solve it? The most common, and simplest way is to solve the conflicts manually.

To solve conflicts manually there are some tools that may help you (like git mergetool, or many others), but I honestly don’t like to use those tools. Maybe I just never invested enough time to make me like them, but I prefer to use a simple text editor. But feel free to have a look at them!

So, how can we find a conflict? It’s simple, a conflict is always something like:

<<<<<<< HEAD

file content in current branch

=======

file content in the branch you are trying to merge from

>>>>>>> other-branch

- Edit the file to match the desired result

- Delete the conflict markers

- (git) add the conflicted file

- Commit the result

And voilá, it’s done. Simple, right? Well, maybe sometimes you will need to call your colleague to understand how to solve the conflict, but this is the principle behind solving merge conflicts.

Solving conflicts using git itself

Git also provides some default merge strategies to solve the conflicts.

For instance, you can ask git to always keep your changes in case of conflict (using the --ours flag), or to always keep the other branch changes (using then--theirs flag).

Other resources on merge conflicts

Merge conflicts are one of the most dreadful subjects around git. So it’s not surprising there are tons of available resources on how to deal with conflicts.

Here’s a list of some I found useful:

- https://www.git-tower.com/learn/git/faq/solve-merge-conflicts

- https://confluence.atlassian.com/bitbucket/resolve-merge-conflicts-704414003.html

- https://help.github.com/articles/resolving-a-merge-conflict-using-the-command-line/

- https://githowto.com/resolving_conflicts

Checkout

This command is probably one of the most confusing commands for git users. The git checkout command can be seen as the command that will restore a specific version. A version can be specified by a branch name (the HEAD of the branch = the last commit on the branch), a specific commit, or a tag.

$ git checkout myBranch

Switched to branch 'myBranch'

$ git checkout myTag

Note: checking out 'myTag'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b <new-branch-name>

HEAD is now at d952dbb7b... <COMMIT TITLE MESSAGE>

$ git co 209665573

Note: checking out '209665573'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b <new-branch-name>

HEAD is now at 209665573... <COMMIT TITLE MESSAGE>

DETACHED HEAD

Have you seen that ‘DETACHED HEAD’ message? What is that? Well, it’s not a big deal, it just means that you are in a state (commit) not referenced by any branch (a commit is referenced by a branch, when it’s the last commit of the branch).

Checkout with file path

Now the confusing part: if you use git checkout with a file path as an argument, the command will revert the specified file from the reference you provided. Just like it was copying the file state on that specific moment, to now.

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: some_modified_file.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

$ git checkout master some_modified_file.md

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Reset

The git reset command is somehow similar to the git checkout command. The confusion between both commands is very common even among experienced git users.

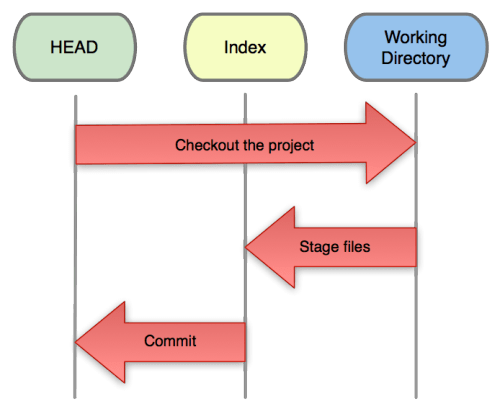

In order to understand the reset command, you need to remember that git has 3 different “areas” (called trees). Each tree is a collection of contents of files, and represents a different state a file can be in:

- HEAD (committed);

- Index (staging);

- Working Directory (the file system version of the file).

The git reset command moves the HEAD to a specified state. This means it will dismiss the commits after the specified state/version. Depending on the flags, the changes introduced by those commits will be moved into some git trees.

There are 3 important flags on git reset:

- --soft

- --mixed (default)

- --hard

Each of them introduces a different behaviour.

reset --soft

It will not change the index area nor the working tree. Meaning, it will keep the Index version, and the previously committed changes will be kept the staging (and working directory) area, ready to be committed or edited.

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

$ git reset --soft 42dd5117e

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 1 commit, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: some_modified_file_since_commit_42dd5117e

new file: some_added_file_since_commit_42dd5117e

reset --mixed

It’s a little further than git reset --soft; it will also copy the specified version into the Index, leaving only the Working Directory untouched. This basically means the changes won’t be in the staging area, as it would happen with the --soft flag.

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

$ git reset --mixed 42dd5117e

Unstaged changes after reset:

M some_modified_file_since_commit_42dd5117e

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 1 commit, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: some_modified_file_since_commit_42dd5117e

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

some_added_file_since_commit_42dd5117e

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

reset --hard

Finally, the --hard flag will simply make the committed changes to be deleted. This means you will revert the current state to a specific commit.

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

$ git reset --hard 42dd5117e

HEAD is now at 42dd5117e random commit message

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 1 commit, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

nothing to commit, working tree clean

More about reset

That is basically it. The reset command overwrites the three git trees in a specific order, stopping when you tell it to. In a more technical way, it consists in the following steps:

- Move branch HEAD to specified version (stop if

--soft) - THEN, make the Index look like that (stop here if

--mixed) - THEN, make the Working Directory look like that (will do only if

--hard)

Boom. You are now a reset master.

Have a look at these resources for a deeper understanding of the reset command:

- https://git-scm.com/blog/2011/07/11/reset.html

- http://blog.plover.com/prog/git-reset.html

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/resetting-checking-out-and-reverting

- https://code.tutsplus.com/tutorials/how-does-git-reset-work–cms-28410

reset with file path

Ups, there’s still one reset variation we did not approach yet: git reset with a file path.

When you pass a file path as an argument to git reset, git will copy the specified version of the file (HEAD by default), and copy it to the staging area. As an effect, if you modified and added to staging file1, and if now you type

git reset (HEAD) -- file1

git will copy the file1 version from HEAD and copy it to the staging area, leaving the working directory the same; meaning it will simply unstage your changes to file1.

Checkout vs Reset

So, aren’t checkout and reset the same? No, they have some subtle differences. The confusion comes from the fact that both are used to get a previous version of your project (or just some files). Still, the commands operate on different git areas/trees.

- git checkout without file path is used to change branch, or to a specific commit/tag;

- git checkout with file path is used to get the file version from a specific reference (branch, commit, or tag) into the working directory (not staged);

- git reset without file path is used to ‘delete’ commits since the specified reference, and their changes, from HEAD (and possibly from other git trees, depending on the flags used);

- git reset with file path will copy the file from the specified reference into the staging area.

As always, Stackoverflow has a very detailed answer for this question. Even better, is the summary table written by Atlassian:

| Command | Scope | Common use cases |

|---|---|---|

| git reset | Commit-level | Discard commits in a private branch or throw away uncommited changes |

| git reset | File-level | Unstage a file |

| git checkout | Commit-level | Switch between branches or inspect old snapshots |

| git checkout | File-level | Discard changes in the working directory |

Conclusion

Wow, this became a little bigger than I expected…

With this post you should be able to understand git to work by yourself in a project under git. I tried to explain all the concepts about some of the most important topics on git for now:

- the powerful branching mechanism that allows you to have independent development paths for features and hotfixes;

- the log system that allows you to have a quick look into the past changes;

- merges between branches, and how to solve the dreadful merge conflicts;

- reverting changes using reset and checkout, and the differences between both.

As you can see, git can be a powerful tool if you invest some time in learning it (yes, unfortunately it’s not the easiest dev tool to get started with). But my recommendation is to just go for it, and try to better understand one command every week, and in no time you will feel really comfortable using it.

Here are the already available parts of this Git series: